What’s a nerd?

My husband and I have an ongoing friendly debate about who was nerdier as a child, which always gives way to a debate about what actually makes one a nerd.

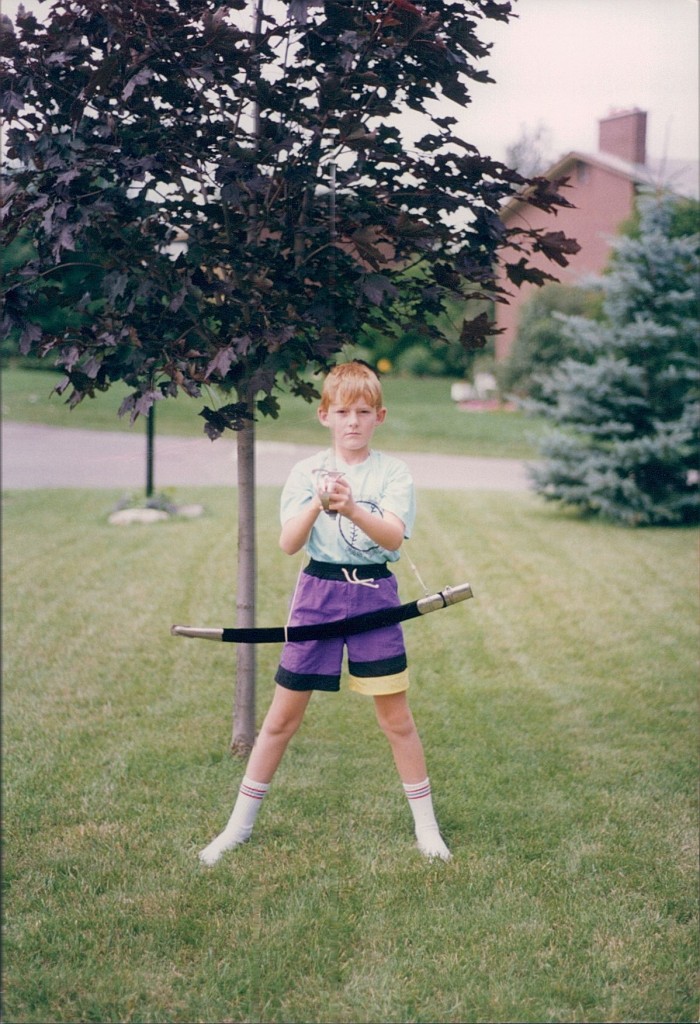

Al advocates for a more narrow, traditional definition of the word “nerd.” He’s a nerd originalist. In his book, a nerd is someone who is interested in most or all of the following: science fiction (defined broadly to include the Star Wars franchise, among others), fantasy role playing games (with Dungeons and Dragons being the most obvious choice for the budding young nerd), space travel, math, and certain video/computer games. Also, weapons.

My definition of nerdiness, however, is concerned less with one’s specific interests than with how different one’s interests are from those of one’s peers, especially in middle and high school. This goes beyond mere social alienation: I mean, if nerdiness could be measured by how alienated one felt in middle school, then I would be the biggest nerd to walk the Earth. But it takes more than being picked on to be considered a nerd, since one can be bullied or feel out of place while also having completely mainstream interests. I think nerdiness also entails a passion about things that others of your age are not into.

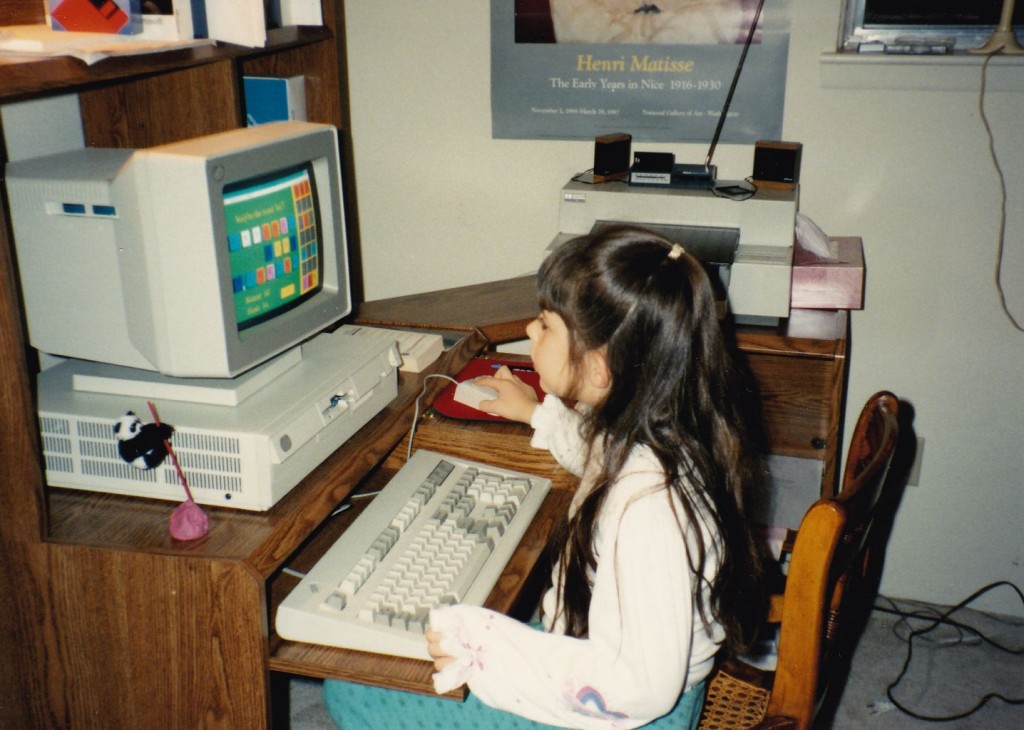

By my husband’s definition of nerdism, young Stephanie would definitely not be considered a nerd. But here, for your consideration, is a short list of things I was really into in middle school:

- Band (I played clarinet)

- Manga and anime (there’s a BIG difference, you guys – just ask 12-year-old me), especially Ranma 1/2

- Chinese language movies and literature

- The Civil War (not the cool band — the war)

- Monty Python

- The Beatles

- Egyptian mythology

- Knitting and latch-hooking

- Teddy bear conventions (yes, this is a thing)

- The Redwall books, by Brian Jacques

- Dog breeds, cat breeds, horse breeds, bird breeds

- Weird Al Yankovic (I was a member of his fan club, the Close Personal Friends of Al)

I’d also like to add that in middle school, I was a subscriber to Cat Fancy, Dog Fancy, Ellory Queen Mystery Magazine, and a quarterly Beatles fan magazine that was sent to me in Michigan via air mail from England. I asked for the subscription for my birthday. My interests as a middle schooler were not necessarily what one would call “tweeny.”

Al, meanwhile, was into, among other things, creating pen-and-ink labyrinths for his friends, playing Magic the Gathering, and reading sci-fi epics.

So — who’s right? Who was nerdier? Could young Stephanie’s collection of esoteric and now-embarrassing interests be considered nerdy, despite the lack of sci-fi involved? Or is Al the true nerd here and I was just, what, autistic? It’s hard to say.

It’s also hard to say why we are both so eager to prove our cred as nerdy little kids. Perhaps because we like to think we’ve come a long way (we haven’t). But perhaps also because being a nerd carries a bit of cache these days. People like to brag about being “huge nerds” about x, y, or z, whether it’s true or not. Claiming to be a nerd proves that you’re passionate about something, that you’re not a follower, that you’re plugged into interests that others are only dimly aware of — these days, being a nerd is almost the same thing as being a hipster. People use both terms — nerd and hipster — derisively, but let’s be honest, there are plenty of people who secretly aspire to both. Plus, let’s face it, if you weren’t a nerd in middle school, you were probably cool in middle school, and we all know what happens to kids who were cool in middle school: it’s all downhill from there, I’m afraid.

Since I’ve met Al, his brand of nerdiness has rubbed off on me. I have read all five books in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, I’ve seen at least part of two Star Wars movies, I know what a Dungeonmaster is, and I’ve watched two and a half torturous seasons of Battlestar Galactica. So I guess I’m moving toward traditional nerd-dom, although it’s not where I feel most comfortable.

I’d like to think that my sprawling collection of odd interests has rubbed off on Al, too, but I’m not sure that’s true. I’ve forced him to listen to a couple of the comedy podcasts I like (including this one) and have convinced him to read a couple of the books I love (such as these), but my influence on him has largely been a corrupting one – I’ve mostly just introduced him to reality TV and crime.

Ah, well. Maybe we can agree to disagree on what a nerd really is. I suppose I prefer to think of myself as a nerdy child because the alternatives are too disheartening. In any case, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve encountered more and more people who are into the weird things that I’m into. This has happened organically, both through the magic of the internet and in real life. Turns out that a lot of smart, funny adults were also into a bunch of weird crap as kids. Odds are, I probably wasn’t the only eleven-year-old who used to tape reruns of Ready, Steady, Go on VHS and rewatch it over and over again. I think.

Anyway, I think it’s safe to say that when Al and I have kids, they’ll be free to explore a wide range of interests, nerdy or not. As long as they’re not cool in middle school, we’ll be happy.

Definitely band, manga, Monty Python, and Weird Al qualify you. Sci-fi would, too, if you were into it. I might even say that being into things that not even other nerds were into (manga) makes you even more nerdy. Sorry, Al.

Thanks, Dean!

I think you guys are arguing about a nerd/geek distinction here. You were focused on things that interested you even if they weren’t traditional age-appropriate pursuits. You developed strong passions and knowledge about those areas. That makes you a geek.

Al was a more traditional nerd. He took his tastes (and apparently his fashion sense) from a subculture that had well-defined boundaries – including D&D, MtG, Star Wars, etc. Geeks tend not to have as well-defined and broad subculture so they are forced to be more extroverted to make connections and create their own communities based on interest. I’ve found that even as these interests change, Geeks tend to self-identify based on the things about which they are passionate.

Nerds don’t need to create community in the same way but also tend to have more of an outsider identity. As their tastes change, nerds continue to feel a sense of not-belonging and are more likely (as far as I can tell) to identify not based on their interests but on their outsider-status.

And this is why you have this ridiculous situation where Harry Potter and Comic Book movies are as mainstream as possible, much of nerd culture is firmly in the mainstream, and yet nerds still feel marginalized. Suck it, nerds.

Yeah, suck it nerds!! Thanks for this distinction. My cousin actually asked me what the difference between “nerd” and “geek” was and I didn’t know what to tell her, so this makes sense to me.