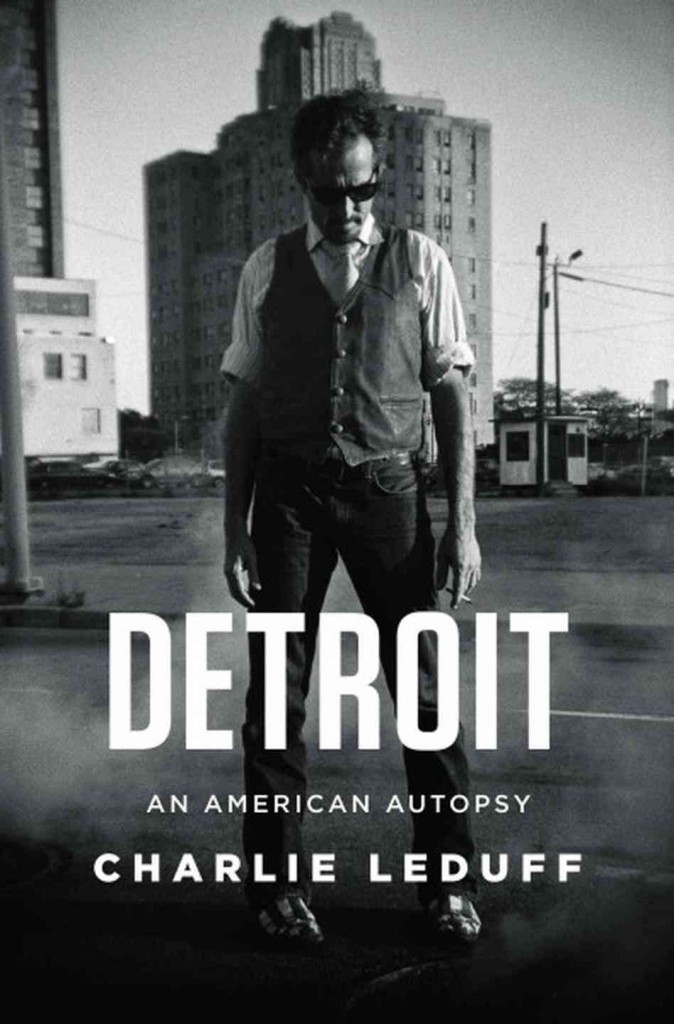

Book review Tuesday: Detroit, An American Autopsy, by Charlie LeDuff

I grew up eight miles north of Detroit – eight miles north of Eight Mile Road, the dividing line between the city and the suburbs – in a comfortable, cute, safe, suburban city called Birmingham. Our little city’s neat streets were lined with trees, kids played outside, and everyone drove an American car. Birmingham was well-off: in our downtown, we had an Anthropologie, a fancy movie theater, and a number of boutique coffee shops. It was nice. And it was a far cry from Detroit, a city that was sinking into post-industrial decay even when I was a child in the 1990s. Detroit was where most people’s parents worked – my dad worked at the famous – and once quite grand – Renaissance Center for years – but the city wasn’t somewhere we went often, except for the occasional hockey game or show or dinner in Greektown. Mostly, Detroit was a place we avoided. And by the time my parents moved out of Michigan in 2002, when I was a sophomore in college, the city had really gone to hell – or so we thought. Then the financial meltdown of 2008 happened, the auto industry tanked, and Detroit reached yet another low. And today, Detroit and its people are still struggling, and very little seems to be improving.

Charlie LeDuff is a journalist who worked for the New York Times before quitting and rediscovering his roots in Detroit, where he began working at the Detroit News in 2008. The guy’s a bit of a wild card. In his book, he doesn’t try to hide his “demons,” and in a way, his instability reflects his surroundings: a structure on the verge of crumbling once and for all. In Detroit: An American Autopsy, LeDuff gives an unsparing run-down of what’s ailing Detroit, and there’s a long list. This is not a book for Detroit optimists. This is a book for Detroit realists, who fear for the people of Detroit, people who have been abandoned by their local, state, and federal governments, their industries, and their leaders, and have been left to fend for themselves with no resources.

In the beginning of the book, LeDuff explains Detroit’s significance in the national imagination, despite its current state of decay:

And it is awful here, there is no other way to say it. But I believe Detroit is America’s city. It was the vanguard of our way up, just as it is the vanguard of our way down. And one hopes the vanguard of our way up again. Detroit is Pax Americana. The birthplace of mass production, the automobile, the cement road, the refrigerator, frozen pears, high-paid blue-collar jobs, home ownership and credit on a mass scale. America’s way of life was built here… Today, the boomtown is bust. It is an eerie and angry place of deserted factories and homes and forgotten people. Detroit, which once led the nation in home ownership, is now a foreclosure capital. Its downtown is a museum of ghost skyscrapers. Trees and switchgrass and wild animals have come back to reclaim their rightful places. Coyotes are here. The pigeons have left in droves. A city the size of San Francisco and Manhattan could neatly fit into Detroit’s vacant lots, I am told… At the end of the day, the Detroiter may be the most important American there is because no one knows better than he that we’re all standing at the edge of the shaft.

LeDuff examines the causes for Detroit’s downfall, noting that “Detroit’s slide was long and inexorable,” and considers a number of possible culprits: “white racism and legal mortgage covenants that barred blacks from living anywhere but the most squalid ghettos;” “postwar industrial policies that sent the factories” out of the cities; the 1967 race riots and the subsequent “white flight” to the suburbs; the policies of Mayor Coleman Young, the city’s first black mayor, “and his culture of corruption and cronyism;” the “gas shocks of the 1970s, which opened the door to foreign car competition;” Clinton-era trade agreements that “allowed American manufacturers to leave the country by the back door;” and the greed and mismanagement of the UAW (the auto-workers’ union).

He also looks closely at the consequences of this spiral downwards: a city riddled by violence and left without basic resources for public services. The firehouse he visits has no fire poles and no engine; children are told to bring toilet paper with them to school; and the police don’t have patrol cars. Compounding all of this is the outrageous corruption at the highest levels of local government. LeDuff discusses in depth Kwame Kilpatrick, the self-styled “hip-hop mayor” of Detroit who, just last week, was found guilty in federal court of “a raft of charges, including racketeering, fraud and extortion.” This was not Kwame’s first brush with the law. In 2008, the Detroit Free Press uncovered, as LeDuff explains, “a cache of text messages showing that [Kilpatrick] was a criminal and a pimp.” LeDuff lays out the situation succinctly:

Kilpatrick had denied in a court of law that he had fired the police department’s chief of internal affairs because he was getting too close to an alleged sex party at the mayor’s mansion – where rumor had it that a stripper named “Strawberry” was beaten silly with a high heel by the mayor’s wife.

Strawberry – real name Tamara Greene – later turned up murdered.

Kilpatrick had also denied in court that he had an adulterous affair with his chief of staff, an old girlfriend from high school. The text messages, however, confirmed that not only was Kilpatrick carrying on with his chief of staff, he was a crook who was looting the city and a letch who bagged more tail than a deer hunter.

Worse still, the texts revealed that Kilpatrick secretly spent $10 million of the people of Detroit’s money to make the internal affairs whistleblower go away.

Yeah. This is the person who was elected as mayor twice by the people of Detroit. For a good rundown of Kwame’s antics, check out this extensive Wikipedia entry. I found it interesting that after Kwame was convicted, finally, last week, some of the jurors commented that they had, in fact, voted for him. The New York Times states: “Another juror said she had voted for Mr. Kilpatrick twice in elections. ‘I was disappointed having done that,’ she said. ‘Sitting on this trial for the last six months, I really, really saw a lot that turned my stomach.'”

Yikes.

LeDuff doesn’t just spend time examining corrupt government officials and greedy auto execs, he also delves into the lives of the individual people trapped in the Detroit quagmire, many of them sucked into endless cycles of violence against their will. It is heart-wrenching and terrible, and the book leaves you wondering what might be done. LeDuff doesn’t know, either, it seems:

Detroit, I am sure, will continue to be. Just as Rome does. What it will be and who will be here, I cannot say. The unnecessary human beings will have to find some other place to go and something else to do. The Great Remigration south, maybe.

So, we’ll see what happens. I hope Detroit can slash and burn and cleanse itself of the corruption that has plagued it for the last several decades. I hope it can start afresh. But…we’ll see. In the meantime, I recommend LeDuff’s book for anyone who is curious about what is actually happening in Detroit today. It’s a fascinating – and deeply depressing – read.

Leave a Reply